Systemic Disempowerment of Third Parties

By Amelia Butler, Nikita Pande, Avigail Katz

Third Parties’ Importance to Democracy

Out of the millions of state and national elections in U.S. history, third-party candidates—those who do not affiliate with the Democratic or Republican parties—are estimated to have won only a few thousand races. This figure includes only the elections in which they were able to participate, a fraction of those accessible to their two-party counterparts. This limited participation is primarily due to the dominance of the two-party system as the political norm in local, state, and federal elections.

While the two-party, “winner-takes-all” system does offer certain advantages—it encourages moderation, provides political stability, and simplifies the voting process—its drawbacks—increased polarization and political stagnation—are significant and potentially detrimental to the very essence of a fair democratic system. Ultimately, the two-party system systematically disempowers third-party candidates.

Beyond the candidates themselves, the two-party system harms the very essence of democracy. When two parties’ platforms do not comprehensively address a citizen’s ideals, they have no option but to pick the lesser of two evils, effectively delegitimizing the process of democracy. Conversely, the presence of third parties can make space and advocate for additional causes and agendas that appeal to many voters, yet are typically overlooked. Thus, it allows everyone a chance to participate in democracy without compromising their beliefs in order to fit into one of the two-party system’s boxes.

Structural Flaws of the Two-Party System

Though the Democratic and Republican parties only took their respective seats as the main contenders of the two-party system in the 1850s, the United States has relied on a two-party system since its founding, with the Alexander Hamilton-led Federalists and the Thomas Jefferson-led Anti-Federalists beginning to build coalitions during George Washington's presidency in the 1790s. Thus, despite no explicit mention of political parties in the United States Constitution, and with Hamilton explicitly referring to political parties as the “most fatal disease” of popular governments, the two-party system is deeply embedded at every level of the United States political system.

Single-member districts, “winner-takes-all” approaches, and campaign financing laws that often favor the two major parties make it very difficult for third parties to win representation. This is due in part to voters not wanting their votes to be “wasted”. If the candidate voters want to vote for has seemingly no chance of winning, then the “winner-takes-all” system makes it so that those who vote for that candidate essentially “throw away” their vote. So, in order for voters to have the possibility of their voice having influence, they must vote for one of the two main contenders. This system not only silences the millions of voices who voted for the losing parties but also diminishes voter turnout and trust in the political system among those who live in “safe” states, given the illusion that no matter how they vote, their state will always have the same political outcome. Thus, it gives voters in “swing” states far more political power than the rest of the country.

This two-party system is evidently structural and not ideological, as candidates effectively use the parties as a method of running for office, while maintaining vastly different agendas on social issues that remain within the theoretical margins of the party. This is exemplified in the ever-changing nature of party stances over the years. For example, Democrats officially opposed gay marriage until 2012, as well as vast differences in social stances between leading Democrat candidates themselves (like Kamala Harris and Zohran Mamdani).

Accordingly, the primary election system does allow for new ideals to come to light by enabling those who wish to challenge current parties to compete for a nomination within one of the existing large party structures, rather than forming a new party. Still, if the aim is to create a stage where all ideas have the chance to take hold and be voted upon, then introducing third-party candidates outside of the current Republican-Democrat framework is crucial.

Alternatively, an article from Boston University states that third parties typically “sting, and then they die because one of the major parties appropriates their message. That’s kind of the role of third parties—they can produce important changes in the political system. But none in the last century has ever threatened to take power.” This is not necessarily a bad thing if third parties can act as a voice to a mass issue that is later picked up on and appropriated to fit the mainstream agendas of one of the two major parties.

The caveat here is that it takes major funds, time, and resources to run as a third party–something that is even less likely to occur and build upon if the only understood goal is to get one of the two major political parties' attention.

Barriers to Third-Party Success

While it is extremely important to maintain third-party civic participation, a multitude of barriers prevent candidates from gaining traction in elections. Ballot access laws, which are laws limiting which citizens are eligible to run for office, have only gotten stricter. In 2012, about one-third of all state House and Senate candidates ran unopposed. These regulations complicate candidate registration for Democrats and Republicans, but are exponentially more difficult to fulfill for third-party candidates with less influence and resources.

Another major disadvantage for third-party candidates is the obscurity of the process. Campaign spending laws differ from state, meaning that there is not one singular standard nationwide. This information tends to be most unfamiliar to emerging third parties who are relatively new to the civic system. Players cannot play the game if they do not even understand the rulebook. The U.S. does not mirror other countries’ uniform, equitable campaign processes, like Britain’s rules of allowing every candidate two free mailings to all the voters, and every candidate getting a certain amount of free TV and radio time. Rather, the U.S. Supreme Court is inconsistent with its rulings, clouding the baseline federal rules. In certain states, candidacy requirements are excessive. North Carolina, with a population of about 9.8 million, requires almost 90,000 signatures, a hefty proportion that smaller parties struggle to obtain.

Political debates are one of the most effective ways for candidates to get their campaign out there and convince voters, but they are also often barriers to the success of third-party candidates. Headed since its creation in 1988 by former chairs of the Democratic National Committee and Republican National Committee, every aspect of presidential debates is usually managed by the two major parties. Democrats and Republicans prevent discourse on progressive topics and block third-party candidates from participating in debates. They instated a rule that candidates must rack up at least 15% of the votes in opinion polls to be invited to the debates, excluding almost all third-party candidates who do not have comparable resources to campaign before debates. This rule is still in place despite three polls in 2016 finding that a majority of Americans wanted two third-party candidates in the presidential debates. Subsequently, the Green Party teamed up with the Libertarian Party to file two lawsuits against the Commission on Presidential Debates, advocating for them to open the debates to third parties. Unfortunately, these lawsuits were unsuccessful, and the fight to increase third-party inclusivity in debates continues.

Funding for the Commission on Presidential Debates is derived from corporations, which have donated millions of dollars to Democratic and Republican candidates to sway decisions about corporate regulations. Notable presidential debate sponsors in the organization’s history since 1992 are tobacco giant Phillip Morris and brewery business Anheuser-Busch. With the amount of influence sponsors have over presidential debates, they prefer to only invite the two traditional parties because third-party progressive ideologies aim to diminish corporate power. Corporations utilize debate sites as marketing opportunities against third-party policies. For example, Anheuser-Busch constructed informational booths to disseminate pamphlets denouncing “unfair” federal beer taxes at the 2000 presidential debate. During this debate, Washington Post reporter Dana Milbank reported that Green candidate Ralph Nader had not even been granted access to the premises, despite possessing a ticket.

Debates for other offices at the state and city levels are usually overseen by media outlet sponsors. However, Democratic and Republican candidates, especially incumbents, mostly decide the terms that must be met in order for them to attend the debate. Media outlets seeking the best news story bend to their will. Among these are the exclusion of other third-party competitors besides their major party counterparts, to minimize their competition and maximize their speaking time. Often, requirements to participate in debates include excessive campaign financing impossible to obtain for third parties. In December 2014, the “Cromnibus” must-pass spending bill went to Congress, which outlined a tenfold increase in the amount of money citizens can donate to party committees: a maximum of $777,600 per year or $1,555,200 per two-year election cycle for a single individual. The maximum for a couple is $1,555,200 per year or $3,110,400 per two-year cycle. Notably, only 0.1% of all tax returns in 2011 showed an income of a million dollars or more, limiting the feasibility of attaining that requirement for less influential parties. The U.S. government takes minimal steps to increase inclusivity in campaigns compared to most modern democracies, which provide significant government subsidies for party activity, typically through funding and/or free access to public or private media.

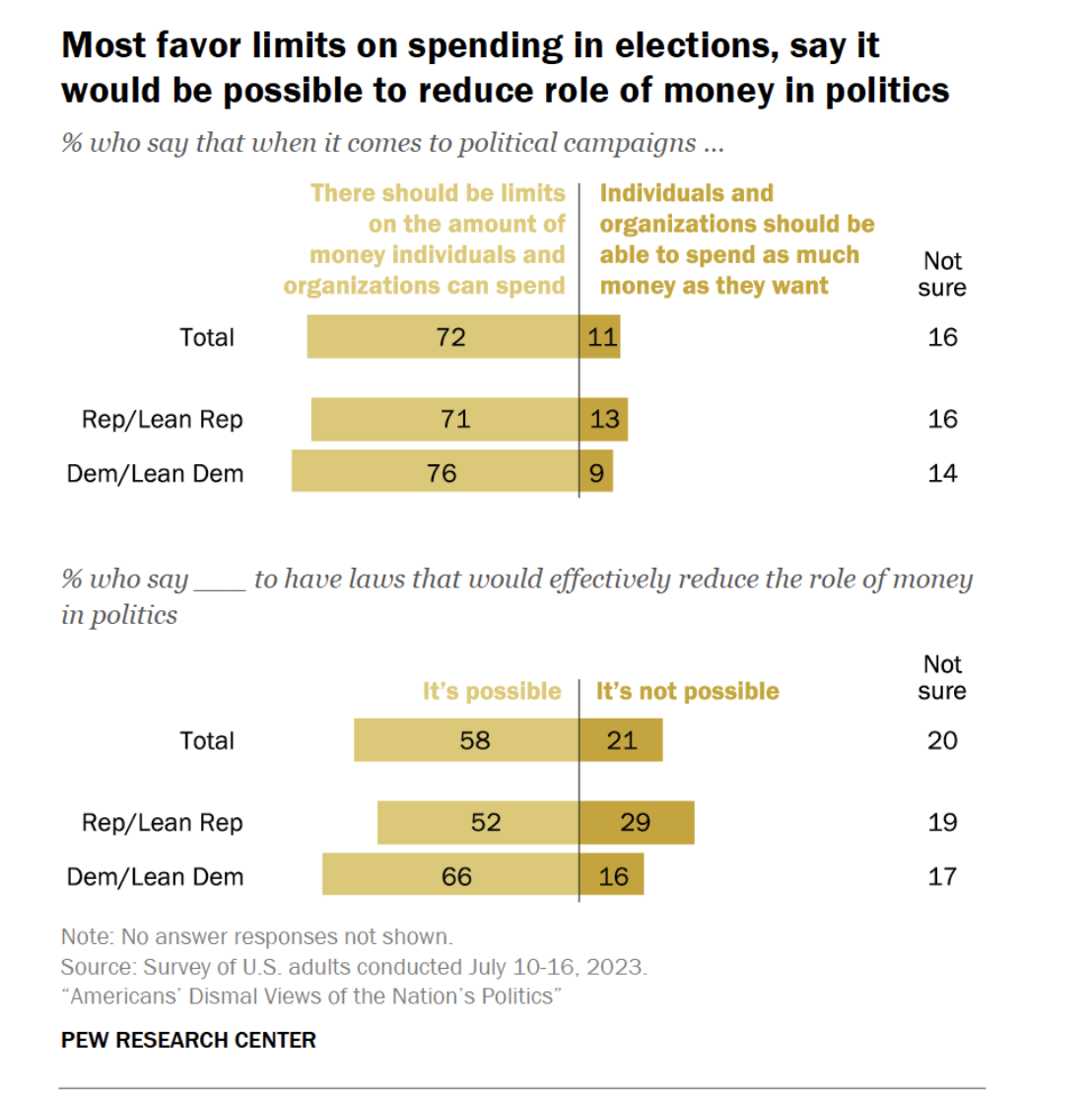

This corruption of political institutions through financial means is widely denounced by the American public. A 2023 Pew Research study states that 72% of the public say there should be limits on political campaign spending by individuals and organizations, since wealthy individuals possess more influence due to their disproportionate ability to fund candidates of their choice. The study goes on to find that almost 58% of Americans believe that it is possible to have effective laws that would reduce the role of money in politics, while 21% say it is not and 20% are unsure. However, efforts to pass publicly funded campaign legislation have been struck down. The systems in Massachusetts and Portland were later repealed, while Vermont’s was struck down by the Supreme Court on the basis of the First Amendment. Wisconsin’s program lost funding at the hands of the 2011 state legislature. However, it is possible: comprehensive public funding systems have been running smoothly in Arizona and Maine since 2000.

Methods of Reform

The current campaign and voting systems require reform in order to end the disempowerment of third parties. Many Western European democracies have used proportional representation to level the playing field for all political parties. Proportional representation seeks to combat the lack of true representation under a two-party system by allocating legislative seats to political parties in proportion to the number of votes they receive. In the United States, candidates can win an election by a very small margin, but as long as they received more than 50% of votes, they act as 100% of the representation. Therefore, the use of proportional representation has the potential to combat the winner-takes-all style of electoral politics. This will directly benefit third parties for several reasons.

Proportional representation may alleviate concerns about wasting votes on third-party candidates. This style of voting ensures that every vote matters in creating a directly proportional system of representation, meaning third parties have a greater chance of winning seats. This encourages people to cast their votes for candidates who are more closely aligned with their personal politics, instead of settling for the “lesser evil.”

Additionally, third-party candidates often face the problem of losing campaign momentum as the Democratic and Republican parties absorb their key issues. For example, the Democratic Party became closely aligned with environmentalist goals and legislation to counteract climate change in the 1980s and 1990s, causing many potential Green Party voters to align with the Democrats instead. Proportional representation would reduce the need for the Democratic and Republican parties to appropriate the messages and stances of third parties. These two main parties would be able to consistently maintain a significant number of seats in government even with the increased presence of third parties. It is likely that the Democratic and Republican parties would still span a broad range of issues to appeal to voters, but proportional representation would give third parties a more distinguished voice in government.

Proportional representation not only allows for more accurate voter reflection and minimizes wasted votes, but also paves the way for increased third-party representation and enables new political ideals and methods to gain traction.

Outside of systemic changes to our democracy as we know it, there are several reforms that could improve the current electoral process. Campaign finance laws create early barriers to success for third-party campaigns. Corporations, unions, and the wealthy are responsible for funding a significant amount of the advertising and creating visibility for Democratic and Republican campaigns through Super Political Action Committees. The unlimited value of independent expenditures through Super PACS disadvantages third parties. In order to level the playing field financially, Citizens United v. FEC must be overturned. Implementing caps on independent expenditures can ensure that elections are not able to be won based simply upon the financial support of powerful companies and unions, but instead places the power back in the hands of the voters.

Furthermore, debates need to be more accessible to third-party candidates and should reflect the diverse nature of politics. Adapting debate formats to support an increased number of candidates allows for third-party campaigns to gain more visibility.

Policy within our system is difficult to ignite, but changing the system itself is nearly impossible without educated voters. It is crucial to not only aim to address issues such as campaign finance inequality, but also to work towards a more equitable process through systematic changes such as proportional voting. We must make our voices heard in this fight against an unequal system of elections as we push for state and national-level reforms to be on the ballot.

Bibliography

Bouranova, Alene. “Is Voting for a Third-Party Candidate Effective or Is It a Wasted Vote? (And Other Third-Party Questions)” Boston University Today. October 28, 2024. https://www.bu.edu/articles/2024/is-voting-third-party-a-wasted-vote/

“Citizens United vs. FEC.” Federal Election Commission. https://www.fec.gov/legal-resources/court-cases/citizens-united-v-fec/

“Fix Our Broken System.” Green Party US. https://www.gp.org/fix_our_broken_system

Greenwood, Ruth. Penrose, Drew. Apau, Deborah. “Proportional Representation.” American Bar Association. May 21, 2024. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_interest/election_law/american-democracy/our-work/proportional-representation/#:~:text=Proportional%20representation%20is%20a%20way,of%20winner%2Dtake%2Dall.

Heninger, Jeffrey. “A Narrative History of Environmentalism's Partisanship.” EA Forum. May 14, 2024. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/F9BBtqFbQnTX5ZvvY/a-narrative-history-of-environmentalism-s-partisanship

Leslie, Laura. “Third parties call on NC to ease ballot access laws.” WRAL News. November 17, 2015. https://www.wral.com/story/third-parties-call-on-nc-to-ease-ballot-access-laws/15115862/

LaLiberte, Laurette. “Two-Party System Pros and Cons: How It Shapes Governance and Policy.” Good Party. October 24, 2024. https://goodparty.org/blog/article/two-party-system-pros-and-cons

“Instant runoff voting.” MIT Election Data + Science Lab. https://electionlab.mit.edu/research/instant-runoff-voting

“Money, power and the influence of ordinary people in American politics.” Pew Research Center, September 19, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/09/19/money-power-and-the-influence-of-ordinary-people-in-american-politics/

“Two-Thirds of Democrats Now Support Gay Marriage.” Pew Research Center. July 31, 2012. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2012/07/31/2012-opinions-on-for-gay-marriage-unchanged-after-obamas-announcement/

“Proportional representation, explained.” Protect Democracy. December 5, 2023. https://protectdemocracy.org/work/proportional-representation-explained/

Pruitt, Sarah. “Why Does the US Have a Two-Party System?” HISTORY. January 12, 2024. https://www.history.com/articles/two-party-system-american-politics

“Presidential Debates Should Include All Candidates that a Majority Wants.” Politics and Economy. https://www.politicsandeconomy.net/presidential-debates-should-include-all-candidates-that-a-majority-wants

Ryan, Tim. “Court Rejects Push to Have Debates Welcome 3rd-Party Candidates.” Courthouse News Service. December 10, 2025. https://www.courthousenews.com/court-rejects-push-to-have-debates-welcome-3rd-party-candidates/

Wayne, Leslie. “In Staging Events, Debate Commission Gets Help From Corporate America.” New York Times. October 13, 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/14/us/politics/14debates.html

Winter, Emily. “Bipartisanship: Barriers to Third-Party Success.” Ave Maria School of Law. July 22, 2025. https://www.avemarialaw.edu/bipartisanship/