Where you Live and how you Register: Voting under the Electoral College System

By Norah Kauper & Chloe Rotonda

The Electoral College is the system the United States uses to elect the president. Each state receives a number of electoral votes equal to its total number of senators and representatives in Congress, which means that every state has at least three votes regardless of population size. Because this system is not based purely on population, smaller states hold more voting power than larger ones proportionally. The students writing this article are from two states that perfectly represent this contrast: Chloe is from New York, and Norah is from Iowa.

Most states, including New York, where I, Chloe, am from, use a winner-take-all system that awards all of a state’s electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote. This process makes votes in “safe states” like New York less influential in determining the national outcome compared to those cast in more competitive “swing states.” Safe states are states that reliably vote for the same political party every presidential election, while swing states are competitive states where either major party has a realistic chance of winning. Although the pattern of safe vs swing states often reflects party lines, it is ultimately about voting predictability—swing states receive more campaign attention because their outcomes are uncertain, not simply because they support a particular party. As a result, the weight of an individual vote can vary widely depending on where a person lives or registers to vote. This uneven distribution of voting power illustrates the complexities within the U.S. electoral system and sets the stage for understanding how individuals decide where their vote will have the greatest effect.

The imbalance of the electoral college works differently for those of us coming to Columbia from outside of New York. The big question we all have to ask ourselves is: do I register to vote in New York, or do I stay registered at home? As a first-year student from Iowa, this is a choice I, Norah, had to grapple with myself. The electoral college complicates this decision when it comes to a presidential election because people may prioritize the difference their vote can make in one state as compared to policies in another. Therefore, a person coming to New York from elsewhere needs to think about where their vote will be most valuable, both to themselves and the causes they believe in.

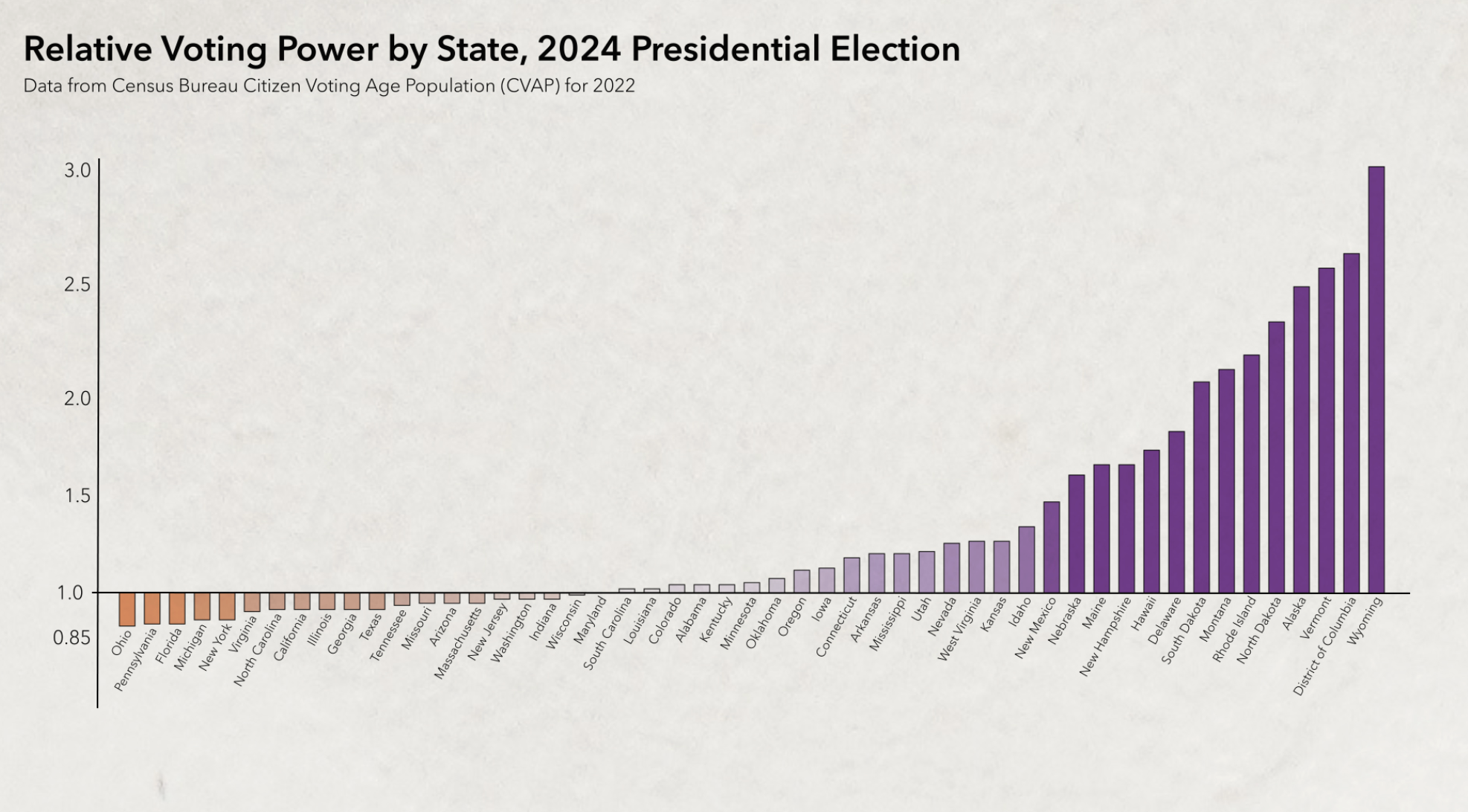

Iowa has 6 electoral votes and a population of 3.2 million, meaning that there are about 533,000 people represented in a single electoral vote. New York has 28 electoral votes and 19.5 million people, meaning almost 700,000 people are represented by a single vote. Using only this data, it would make sense for myself to stay registered in Iowa because my vote quantitatively counts for more at home, at least in regard to the electoral college. There are actually many states with even more individual voting power than Iowa. Wyoming has fewer than 200 thousand people per electoral vote, giving the state drastically more weight than New York.

We are able to analyze this data more scientifically by looking at two ratios: the ratio of voting-age civilians in a state versus the country’s population, and the ratio of electoral votes in the same state versus the total 270. For example, a single person’s vote in Maryland is also “worth” one vote because the number of voting-age people in Maryland makes up 1.8 percent of the country’s voting population, and Maryland’s electoral votes are 1.8 percent of all 270 votes. New York is the fifth least represented by proportion, according to graphs made with data from the Census Bureau. However, it is necessary to point out that the graph displayed below is only relevant to a national election with electoral votes, because state and local elections are determined by districts within the state.

Another factor in determining a vote’s worth is the politics of the swing state. Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Florida may have the lowest valued vote going by proportions, but all of them have been largely influential swing states in the past few elections, especially Pennsylvania. During presidential and other federal election cycles, it's important for students to consider if their vote has the power to tip their purple state towards their party.

However, I think the reason why a person chooses to vote at home or here, in New York, is ultimately due to personal motivation and not power. This is especially true between presidential elections, because local politics take the front stage. Many liberal or leftist Columbia voters were inspired to register in New York only to vote for Mamdani this year, and others chose to remain at home because of their own mayoral elections or propositions.

This brings me back to Iowa. As I discussed previously, the reason why I remain registered at home is less due to my blue vote’s value in a small, red state, and more because I still care about the consequences of elections in my home. Iowa hasn’t gone blue since 2012, and it slowly creeps further into the red every election. On a national level, Iowa is only slightly more powerful than a vote in New York, and I doubt my singular democratic vote will hardly make a difference against the sea of republicans. On a local level, my city is in the most liberal county in the entire state, so my vote won’t change much there, either. Yet, I still want to stay registered in Iowa because I care about who is elected to our school board. The current representative is Republican Miller Meeks, and I believe my vote could help replace him in the 2026 election. In addition, I still believe Iowa could swing blue again. Iowa is also the first state in the country to vote in the primary election, which has historically influenced the primary results nationwide. Despite its many flaws, I love my home state, and having a vote that can help improve it is a privilege I will never give up.

Because the electoral college is flawed, there is truly no way to navigate it perfectly or simply. However, what our differing experiences reveal is that students make the decision of where to register through a mix of structural realities and practical considerations. For Norah, remaining registered in Iowa reflects an ongoing engagement with the political dynamics of her home state. For Chloe, coming from New York—a state whose electoral outcomes are highly predictable—the question has been less about shifting national results and more about understanding how her registration interacts with the state and local elections she participates in while at Columbia. In both cases, the broader point is the same: students weigh identity, policy priorities, and strategic value differently depending on their circumstances. Regardless of where your ballot is cast, elections remain one of the most powerful tools of civic engagement in the United States. The choice of where to register is not about finding the “correct” location, but about ensuring consistent participation in the democratic process.